Some early lessons of 2024 in the energy sector

Conventional wisdom is coalescing on all the wrong things

Not all full-year data is available for 2024, so I will most probably do another post when final numbers are there, but this is the season for yearly reviews and those that I have read have given me a strong desire to argue against what seems to be obvious to mainstream commentators.

Amonts the “certainties” from this year: demand for power is exploding thanks to AI and data centers, nuclear is back, and US oil&gas is saving the energy system (and giving the US an unsurmountable competitive advantage). The FT is a good example of that (here, probably behind paywall).

And yet…

So I’d like to list somewhat different highlights:

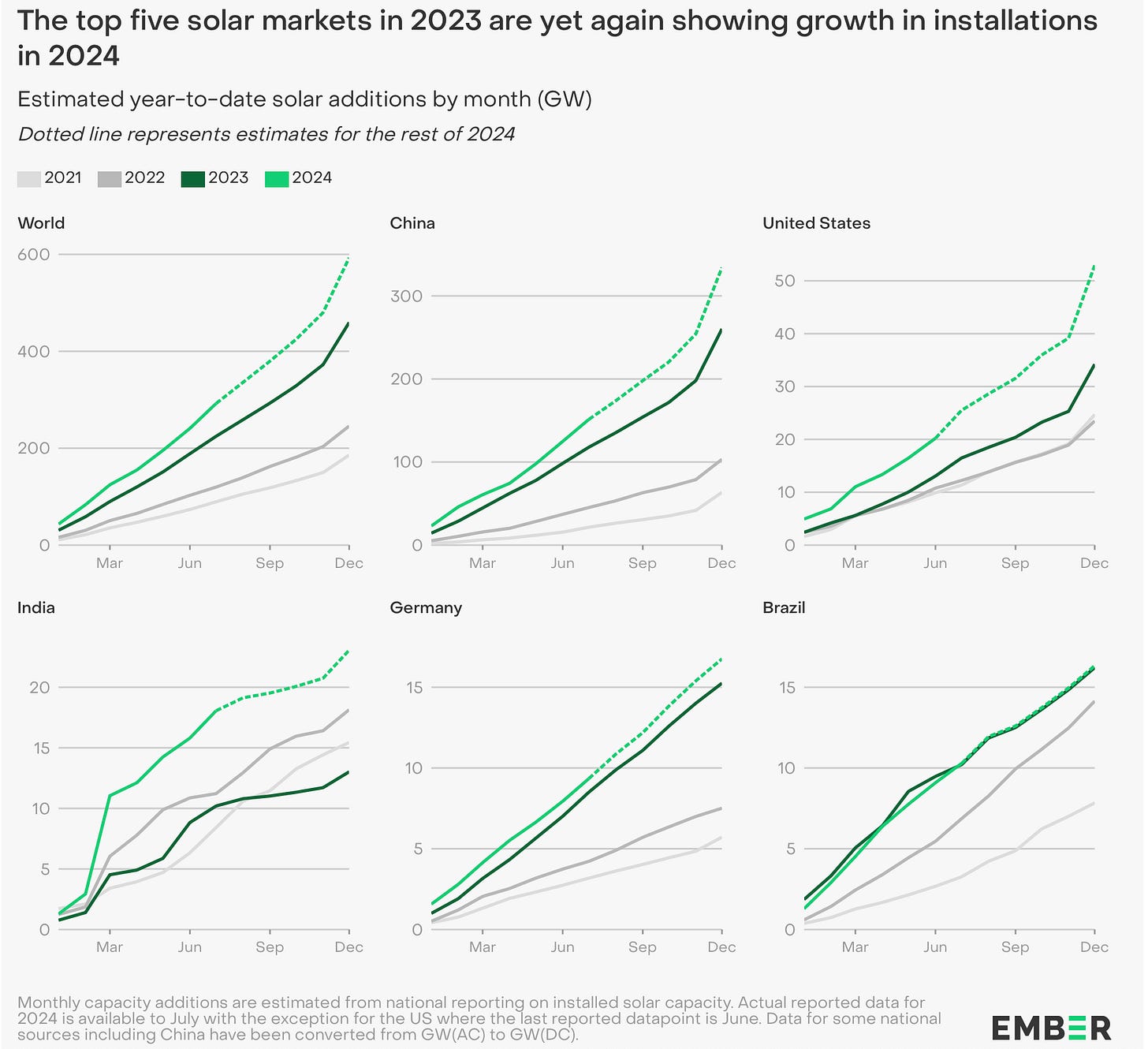

the first is the incredible growth of solar, and the corresponding surplus of electricity we have more and more of the time, as visible through negative power prices

Source: GEM Energy Analytics

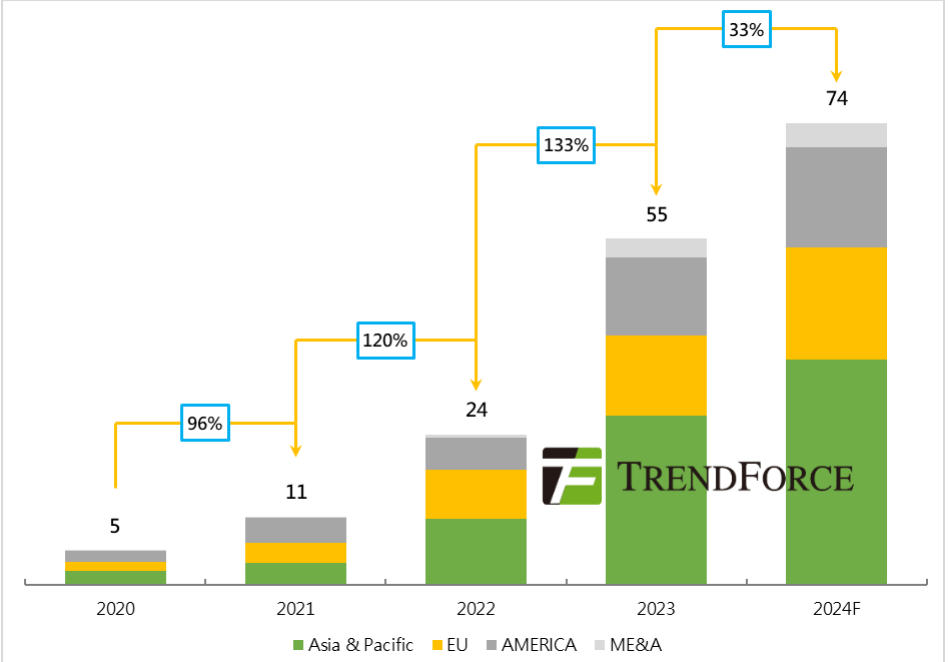

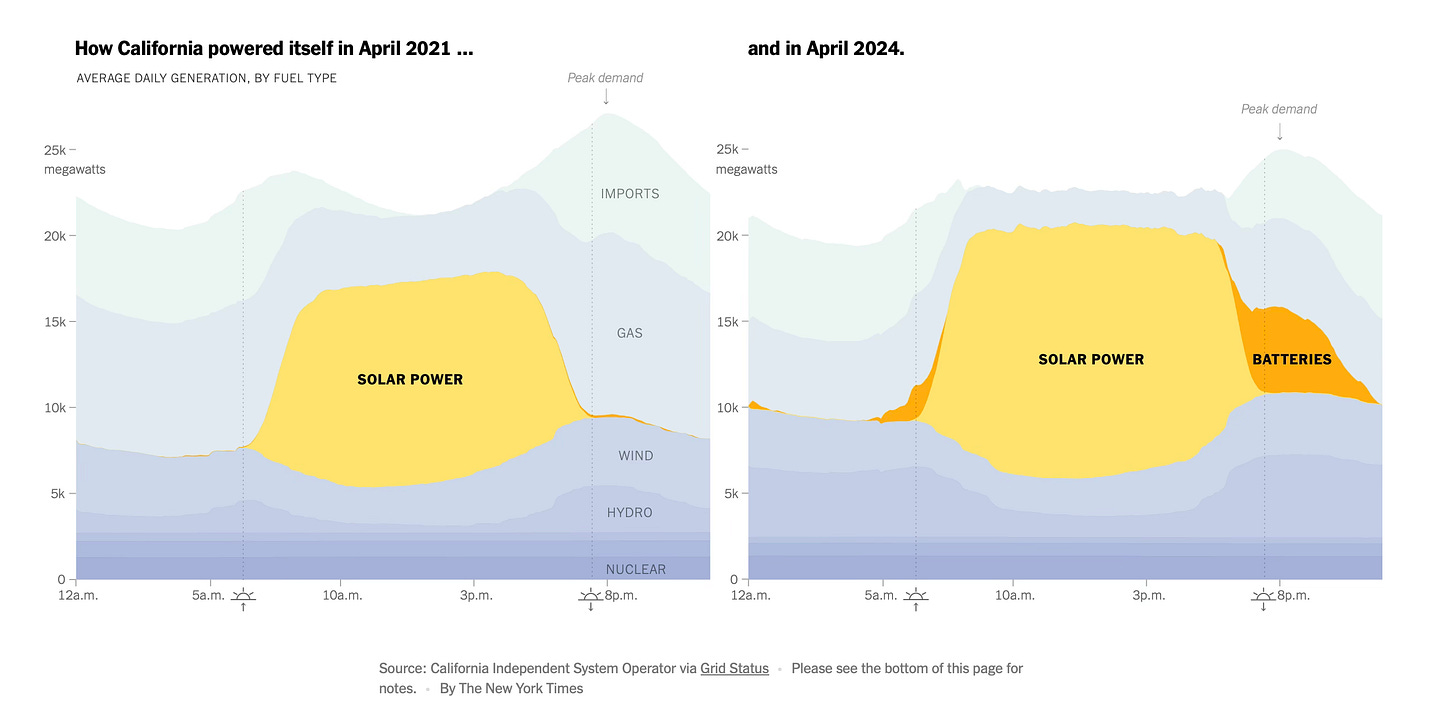

the second is the incredible growth of storage, which is the obvious, and working, answer to the first point - it’s just very difficult with such growth rates to match the two exactly

Global energy storage systems installations in 2024 (in GW). Source: Energy Trend

Source: NYT “Giant Batteries Are Transforming the Way the U.S. Uses Electricity”

the third is that this is the last gasp of nuclear - maybe some people hope to see Flamanville being finally connected to the grid in France, and multiple PR stunts by Microsoft, Amazon et al. (which are just announcements of developments, i.e. highly conditional commitments to purchase electricity) as the start of a renaissance for the sector, but it’s more like a last gasp - in fact 2024 is most likely the year where wind+solar overtook nuclear in the USA, as well as coal.

Source: EMBER (In the same link one can see that in Europe wind+solar have now overtaken all fossil fuel generation).

Flamanville is likely one of the last nuclear plants to be built in Europe. Hinckley Point may be completed at some point in the future in the UK, but even in France the next ones are in doubt, with decisions on future investments postponed.

By the time any new nuclear plant in the West gets build, the transformation of our power systems towards renewables dominance will be over.

the fourth is that demand is actually still shrinking. Despite all the breathless announcements about AI and data centers, overall demand is mostly stable in the US (increasing by 2% in 2024 after decreasing by the same in 2023), and shrinking fast in Europe

Source: Energy Charts

Some are blaming European deindustrialization (and collective suicide caused by crazy green policies and/or naivety about Russia, even if these are two contradictory and inconsistent arguments) but the trend predates the war in Ukraine. The reality is that we are continuously improving industrial processes while moving towards services, and a service economy is less energy intensive than a more primitive one. Even in emerging markets energy intensity is going down fast.

Source: Our World in data

the fifth is that nobody talked about lithium or copper or other critical raw materials for renewables. We’re still talking about oil (but, as the FT noted in their story, even in a year of massive geopolitical turmoil, oil prices did not move much, and, if anything, went down), but the breathless scaremongering about other minerals being unavailable for the energy transition has disappeared together with the collapse in prices, which reflects the normal adaptation of supply and demand in a cyclical sector like commodities to earlier changes in demand.

That brings me to the last trend - the utter rejection of renewable energy by the markets. From public announcements, it seems that everybody wants to exit renewables (see my earlier story on that topic), and in particular stock market investors are loudly cheering the fact that oil&gas companies are reducing their investments in the sector. As it were, I tend to agree that oil&gas companies are not the most relevant investors into renewables - they have expensive capital, as required for their riskier core business, and the returns in lower-risk renewables are more adapted to investors like pension funds or specialized infrastructure funds. But the message “renewables are not appropriate for oil&gas companies” has turned into “renewables are bad investments” in public perception, leading to an unseemly (and in all likelihood, ultimately costly) rush to the exit by players that should know better.

Specialized sectorial players are mostly continuing their ongoing investments in a low key manner, but they are also avoiding splashy new announcements, leading to the continued dearth of buyers. In fact, renewables are so oversold that they have become an amazing buying opportunity, and the handful of remaining players willing to take bets on the sector will earn oversized rewards in the near future. (If anyone reading this has money, I’d be happy to help you find the best opportunities around 😇).

At the heart of that is the fact that renewables briefly became the darlings of the stock markets in 2021, leading to a bubble that has now burst, due to a combination of an unfavorable macro shock with the trifecta of war in Ukraine, inflation and increased interest rates, plus more directly hostile politics from the populists. The resulting pain is leaving a sour taste - plus noisy glee from political opponents. Volatile capital markets are not necessarily the best to finance a sector that requires long term price stability (best offered by bank lending and specialised equity from dedicated funds).

Meanwhile, incumbents (utilities), long used to dominating the debate and government policies have been caught on the receiving end of the anti-renewables propaganda they spewed in the past, and which have been weaponized wittingly or unwittingly by the political opponents of the greens, usually the rightwing populists, who are ascendant right now. So the current debate on energy is highly polarized, mostly tribal, and renewables are on the losing side in the public debate. It does not matter much because the march of solar and batteries is relentless and irreversible, but it makes policy making harder, and investment decisions scarier.

But it’s usually darker before dawn, and I expect that this is where we are in that cycle. It’s time to anticipate things and move to the buy-side!

I should expand my comment on gas prices impacting electricity prices. In Australia, base load is provided by coal fired power plants, which are in the process of being phased out and gas fired generators. Gas fired generators are deemed best suited to quickly meet shortfalls in wind and solar generation and therefore set the wholesale price in such circumstances.

A very interesting article and somewhat contrary to much of the negativity regarding renewables I have been reading over the past year. However, you have not provided comment on electricity prices paid by consumers apart from noting negative pricing is occuring in markets as a consequence of surplus electricity.

My experience in Australia, which has very high penetration of renewables, is that the latter is not translating into lower electricity prices, and in fact the state with the highest penetration of renewables (South Australia) has the highest electricity prices. In part this seems to be due to high gas prices impacting wholesale prices. This is in part being addressed through the large number of big batteries being installed, in line with your analysis, and it has also prompted a review of whether the electricity market in Australia is still fit for purpose.

Another factor is the very high cost of connecting dispersed solar and wind farms to the existing grid. All of the above has prompted a push towards nuclear energy from the opposition party in Australia. Independent economic analysis has shown that the proposal would reduce electricity prices but as you might expect the analysis while sound on one level, is fraught with assumptions and has been met with a frenzied response.

Interested in your thoughts or comment on any or all of the above.

Murray Arthur-Worsop