Note - this is a slightly updated version, edited for clarity following comments by early readers. The map for Blue Stream was added

As I wrote my PhD about the independence of Ukraine (in 1995) and spent 6 months in Kiev in 1994, the current attack by Russia hits very personally. But I also put on my hat of energy specialist - with my career as an energy financier kickstarted by my knowledge of the Soviet oil&gas sector built at that time to write the below.

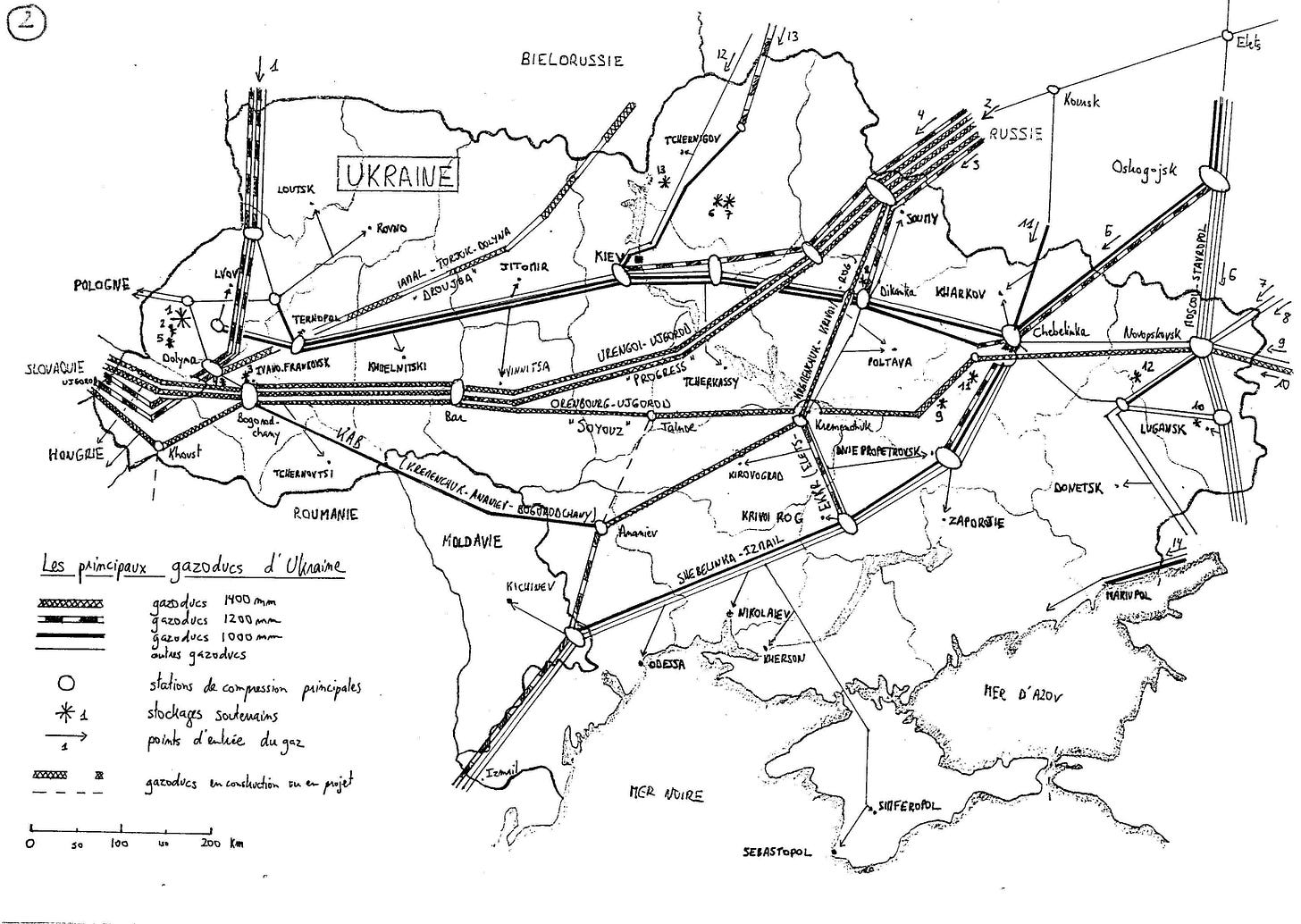

I attach a map of the Ukrainian pipelines in 1994 that I prepared myself at the time from various internal Ukrgazprom (the national Ukrainian gas company) sources. I'm sure they had their own maps, but they were not widely distributed and the people I worked with at the time were really happy to get copies from me (photocopiers and printers were pretty rare in Ukraine at the time, too) and I was asked to keep it really confidential then... The map is no longer fully up to date, but it provides some useful insights on some of the origins of the current crisis.

First: to give some background numbers1. In 1992, Soviet gas production was around 600 bcm/y (billion cubic meters per year) - for comparison purposes that was fairly close in scale to US production at the time, which has increased significantly above that level in recent years. Of that, most was produced by Russia (around 500 bcm/y) and 120 bcm/y was used in Ukraine, plus a similar volume exported to Western Europe, including Turkey, 90% of which transited through Ukraine. So close to 40% of Soviet production was going to or through Ukraine - with responsibility for exports inherited by the Russian entity, Gazprom. Additionally, gas was also transiting via Ukraine to Southern Russia - more on this below. Ukraine, then, and now, was producing around 20-30 bcm/y.

Today, Russia produces roughly 600 bcm/y, exports 180 bcm/y to Europe (inc. Turkey) and 30 bcm/y to Ukraine. Of the exports, only 50 bcm/y now transit through Ukraine, with the rest through other pipelines (in particular the newly built Bluestream to Turkey under the Black Sea, and Nordstream to Germany under the Baltic Sea).

Another point worth noting is that the Soviet gas industry originated in Western Ukraine, before the big gas fields in Siberia were discovered and developed, and a lot of the workers in the Soviet (and then Russian) gas industry were Ukrainian. By the 90s, gas production in Ukraine was in decline and represented only a small part of overall Soviet production. But Gazprom was still very Ukrainian, both in terms of personnel and the importance of the pipeline network in the country, as shown on the map above. An anecdote I was told in Kiev is that during the early 1992 meetings between Gazprom and Ukrgazprom about the export pipelines, the Russian delegation offered to conduct the discussions in Ukrainian, as they all spoke the language, but Ukrgazprom declined, as some of their officials (Soviet bureaucrats shipped from Moscow) did not speak the language… So Gazprom knew Ukraine intimately.

Contrary to Western perception, where the issue became a hot topic only in 2006 and subsequent years, the disputes over Ukrainian (non-)payment for Russian gas started as soon as 1992. Ukraine expected deliveries to continue at Soviet conditions (or at least at the same price as Russian consumers, while Russia wanted to treat Ukraine as an export market and wanted to bring prices in line with other European countries, with payment in hard currency. Gazprom started asking for payment with threats to cut off the gas deliveries to Ukraine, and did implement partial cuts - partial because they needed to keep on delivering, via the same pipeline network, the volumes destined for export. Ukraine simply started using the gas meant for exports. Gazprom had to relent each time and restored full gas deliveries to Ukraine in order not to interrupt its export flows. This happened multiple times throughout the 90s and after - and a lot of the political instability in Ukraine came as a consequence of the strategies used by Gazprom, or Gazprom’s senior management (and we’ll see that the distinction is important), to find a solution to that inability to get paid by Ukrgazprom.

One item that is still relevant today is the gas storage facilities in Western Ukraine, represented by the little stars on the map. This storage capacity is critical for Gazprom’s export capabilities, given the seasonality of gas demand. The only way for Russia to deliver enough gas to Europe in winter (while also providing enough gas within Russia, where it is literally a matter of life and death for the population) is to build up storage in Ukraine during the summer months. That means that the pipelines through Ukraine are used a good part of the year for deliveries within Ukraine which are then exported in winter. Most of the Russian gas exports that still go through Ukraine today (50 bcm/y) are the volumes that take advantage of these facilities, as they provide a cheap way to make additional deliveries in winter, even as Gazprom focuses its export volumes on the alternative routes that have been built in the meantime.

Another point of interest on the map is the diameter of the pipelines. This was relevant and strategic information because at the time, each category of pipeline was typically manufactured - for the whole Soviet Union - in a single plant. A few Ukrainian factories had a monopoly on the fabrication (and maintenance) of certain sizes of pipelines, and a few Russian factories had a similar monopoly on pipelines of deferent diameters. These pipelines were used across the whole Soviet Union, and notably from the gas fields of Siberia to the rest of Russia and then towards Europe. That translated into mutual absolute dependency between the two countries as Ukraine had a chokehold on supplies needed in the Russian part of the gas network, while Russia controlled pipeline supplies for sections of the Ukrainian network.

Such dependencies were acute in the early years of the breakdown of the Soviet Union and forced the two countries to keep on working together to maintain supply chains (a similar co-dependency could be found in the nuclear fuel cycle, necessary for the nuclear power plants in both Russia and Ukraine, with various steps of that process done exclusively in Ukraine and then exclusively in Russia and back again). The dependencies were broken down over the years, as each of the two countries looked for alternatives for the goods coming from the other , or started using in priority the goods that they could manufacture themselves or import.

Russia put a lot more effort in the early years of Ukrainian independence to reduce the leverage Ukraine had on Russia:

For instance, on the right-hand side of the map one can see pipelines that cross Ukraine and go to Southern Russia, making a good chunk of Russian domestic gas consumption then subject to Ukrainian control. In the mid-90s Russia built the Blue Stream pipeline to Turkey, and that was financed by international banks as it provided for new export capacity to Turkey (a fast growing market for natural gas). What most people did not realize was that Blue Stream really was as much a domestic project for Russia to secure deliveries to its Southern provinces independently of Ukraine - a large chunk of the project was actually within Russia even if most public discussions of the project focus on the new export capacity made possible by the section under the Black Sea. The export angle made the financing easier for Gazprom. It is hard to find maps that show the relevant pipeline, but here’s one, from East European Gas Analysis - the area to look at in within the red circle, with the new lines that go South and avoid Ukraine:

In the same vein, it should be noted that Nordstream 1 (also visible on the map above, in the Baltic Sea)) was not meant to avoid just Ukraine, but also, and maybe more importantly, Poland. Poland is actually the only country that successfully blackmailed Gazprom into making something in the order of a billion US dollars in payments to complete the Yamal-Europe pipeline (also visible on the above map) inside Poland (and not all that money went to pipeline construction…), at at time, in 1998, when Russia had very little cash available. (You can google “Gudzovaty” and “Bartimpex” to dig up what little information can be found on this). With this episode in mind, both Russia and Germany, which was receiving most of the gas going through Poland, decided to avoid transit countries, despite knowing that “Molotov-Ribbentrop” would be mentioned at every turn - the bad publicity was still better than depending on Poland for the gas transit.

But moving back to the Ukrainian transit issues: over several years in the 90s, Gazprom failed to get Ukraine to make payments for gas deliveries, and Ukraine used volumes destined for Europe whenever Gazprom tried to cut deliveries to Ukraine, and each time Gazprom relented and restored full gas deliveries. This happened pretty much every year from 1992.

But in 1994, someone at Gazprom had a great idea. If you look at the bottom right of the map, you see a pipeline going to Mariupol directly from Russia. Mariupol happens to be the home of Azovstal, a huge steel plant, one of the largest gas consumers in the world - in the early 90s it used 12 bcm/y - that’s as much gas as France imports from Russia. As a steel producer and exporter, Azovstal had cash and did pay for its gas - to Ukrgazprom, which then did not pay Gazprom. What Gazprom did was to cut off that line specifically, and when Azovstal complained that it *was* paying for the gas (to Ukrgazprom), Gazprom insisted on direct payments. A damaging stand off occurred, until someone came up with the idea of a supposedly independent supplier that would procure gas from Turkmenistan and be paid directly by Azovstal. The notion that an independent supplier could use Gazprom’s pipeline network without approval at the highest levels of the company (and the Russian government) was an obvious fiction, but it was put forward and somehow taken seriously. Crucially, such independent trader was not owned by Gazprom, meaning that the volumes were separated from the broader Gazpom-Ukrgazprom relationship. Gazprom still did not receive any revenue from these volumes - so there had to be benefits somehow going to a few well placed people within Gazprom, as well as Ukrgapzrom and both governments which were needed to authorize the whole scheme.

That was the birth of Itera and all the other shady intermediaries that effectively privatized a part of the Russian-Ukrainian gas trade, generating billions for a few well-connected intermediaries in both Russia and Ukraine (see this article in RFE/RL which discusses the situation in 2002), including some (like the “gas princess”) that would end up playing active roles in Ukrainian politics over the years.

To sweeten the deal for Azovstal, they were offered extra volumes that they could sell on to other local consumers in the area with a mark-up. Various parts of Eastern Ukraine, with all its heavy industry, started receiving their gas via such arrangements, and the gas consumers that were not in the arrangements wanted to have their own direct supplies with “independent” suppliers rather than buying from rival industrial groups in Ukraine. This led to huge fights, in particular between Donetsk-based and Dnipropetrovsk-based organisations, each with their Russian partners, to control that market. The visible part of the iceberg was the political infighting within Ukraine, with the central government in Kiev increasingly sidelined from the gas business and politically captured. This created a very unstable political system, with strong pro-Russian forces actively fighting each other, and with a fourth player being the more nationalistic Western Ukrainians, less involved in the gas disputes, but representing a significant chunk of population. What is essential to note is that none of these players in the gas business were anti-Russian - they were Russian-Ukrainian alliances fighting each other, using the Ukrainian government as a tool. Part of the export capacity of Russian pipelines was effectively partly privatized by these groups, something that could only happen with support at the very highest level in Russia.

In 2006, something else changed: the UK became a net gas importer, realized it had no plan to ensure security of supply, and panicked. After desultory attempts to involve European rules to gain access to storage capacity built and controlled by French and German companies, the country’s politicians found a convenient scapegoat for their lack of foresight: Russia and Gazprom, supported in that by US Vice-President - and cold warrior extraordinaire - Dick Cheney. That was the year when for the first time, the almost yearly brinkmanship between Ukraine and Russia about gas transit became international news and the UK and US actively picked sides and laid the blame on Russia for what had been fights between oligarchs of both Ukraine and Russia.

Suddenly the gas transit dispute somehow became a highly publicized fight between the West and Russia, which was accused of using the “energy weapon”. The underlying dispute between rival oligarchic groups, which (mis)used strategic instruments like gas deliveries to the West, was actually showing either the lack of control Putin had over these tools, or his acceptance of their use for private purpose, but that was all behind the scenes.

Instead, the very public disputes and the black-and-white us-against-them tones initiated by the West allowed him to take further control over Gazprom, and to pick sides in Ukraine - even though the Eastern Ukrainian rivalries were not really solved. Domestic Ukrainian politics continued to be strained, but now with the additional background of having become a battleground between an increasingly assertive Russia and the West.

Today, the only gas transit volumes through Ukraine are those predicated on the storage volume capacity in Western Ukraine and that will not be changed by Nordstream 2, which has been the object of a long debate (and has now been blocked by Germany). Gas is no longer what’s at stake between Ukraine and Russia - volumes have gone down significantly over the years, and Ukrainian consumers now pay close to the market price for the gas they use; transit is also paid for as a service, and some form of equilibrium has been found, even if individuals will still jockey to be the privileged intermediary that gets “first dips” on some of the trade volumes.

GAs remains highly relevant to the relationship between Russia and the West, but this is a different topic - it is Europe’s perceived dependency on Russian gas that made Putin confident enough to attack Ukraine without fear of retribution.

What remains true is that gas has polluted the domestic politics of Ukraine for many years, and undermined its ability to stand up as an independent country. Instead, it has been weakened by internal and international rivalries, with heavy Russian participation, for the control of the domestic gas revenues. These rivalries lead to years of political instability and were then turned opportunistically into a Russia-vs-West fight that prevented Ukraine from achieving any form of sustainable political and economic stability, and have made it a diplomatic and military battlefield.

Further reading on these topics that were published in academic or business papers:

L’indépendance de l’Ukraine, PhD dissertation (in French), 1995.

Fix Gazprom’s Fatal Leak, Wall Street Journal, 31 May 2002

Gazprom's Got West Europeans Over a Barrel, Wall Street Journal, 8 November 2002

Gazprom as a Predictable Partner. Another Reading of the Russian- Ukrainian and Russian-Belarusian Energy Crises, IFRI, March 2007 (PDF)

Policy is the key to security, Fundamentals of the Global Oil and Gas Industry, Petroleum Economist, 2007 (PDF available on demand)

The battle of the oligarchs behind the gas dispute, Financial Times, 6 January 2009

Ukraine versus Russia: the real story, European Energy Review #8, Jan-Feb 2011 (PDF available on demand)

How to get a pipeline built: myth and reality, in Russian Energy Security and Foreign Policy, edited by Adrian Dellecker and Thomas Gomart, Routledge, May 2011

Note that I’m using rounded numbers. Exact numbers can easily be found but do not change the gist of the story.

Maybe it's not obvious, but comments are possible - and I will be around to answer any questions! Private queries can also be sent to jg1789@pm.me

An absolute must-read. Thank you Jerome!