Wind needs to be competitive against the lowest price of gas, not the average (or the current) price

Cheaper and more competitive are not the same

People often ask, sometimes in good faith, why renewable energy producers are still asking for fixed price tariff regimes and other similar mechanisms to avoid the market price if, as is claimed, they are cost‑competitive.

There is actually a simple reason for that:

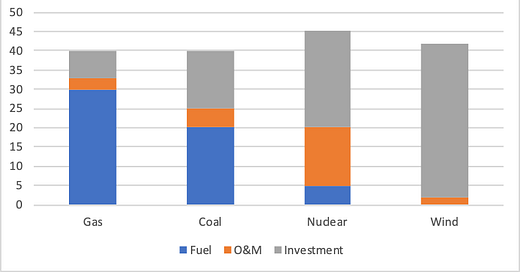

Figure 1: The relative composition of the cost of electricity for different types of plants

Source: IEA World Outlook 2004, adapted by author (a very old source is used on purpose to show that wind has been cost-competitive for a long time - the obstacles to buildup are elsewhere)

Generation costs for wind (like for nuclear) are largely fixed – it is the amortization of the initial investment over the lifetime production of the project. Variable short term costs (operations and maintenance) are very low – as opposed to fossil fuel power plants, whose main cost is the fuel to generate each incremental MWh of power.

And given that fact, wind projects rely heavily on debt, which is the cheapest form of capital and allows them to have a competitive cost structure. Debt is cheap, but it is inflexible in that it needs to be repaid in priority by the project (after only operating costs and taxes), and in regular, fixed amounts, irrespective of what the wind farm produces and at what price it sells its power.

That puts debt‑funded projects at risk during periods when power prices are low, as the project may not generate enough cashflow in these periods to fulfill its short term debt obligations. It does not matter if prices are high enough on average to repay debt, they need to be high enough in every single debt service period, otherwise the project may have to default on its debt and owners are at risk of seeing their asset seized by the banks.

Conversely, gas-fired projects are inherently profitable - most of their cost is linked to the cost of fuel, and they only produce when the price is high enough to justify buying and buying the fuel - in practice the price of the fuel drives the price they will quote and de facto the price of gas ends up driving the price of power: gas-fired plants are price-makers and “surf” on the price of gas.

Figure 2 - the cost of gas-fired vs renewable power plants, and the price of gas

This means that investors will only in wind projects in a merchant context if they are comfortable that the project can withstand sustained periods of low prices – in practice that translates into a requirement that the expected cost of production (LCOE – levelized cost of energy) must be lower at all times for the life of the project than the market prices achieved when gas prices are low. It is not enough that the LCOE of wind is below the expected average price of gas.

Another way to look at this is to consider an adult at the beach, chained to the floor as the tide comes in, while her infant son has floaters. When the tide comes and goes, from 0 up to a height of 2 meters, the height of the adult’s face remains constant at 1.5m, above the average height of the mouth of the infant, which floats a few centimeters above sea level (1.1m). 1.5m is higher than 1.1m, and yet, the infant survives the tide while the adult does not.

There are many good reasons to maintain the spot market as a mechanism to balance power market at every instant, and to ensure that renewable energy is included in the mechanisms that the grid operator uses to ensure the equilibrium or the market and security of supply – this is what has been achieved by using “contracts for differences” rather than feed–in tariffs, as it imposes on renewable energy projects to sell their production on the wholesale markets and follow their rules (on balancing, reactive power, inertia, etc.), while offering to both seller and buyer a stable price for their power production – but such stable price is both necessary to make investments in renewable energy possible and efficient - it actually makes the resulting cost of electricity lower as fixed prices allow to attract cheaper capital.

If derived through competitive tenders, such fixed price CfDs can be considered as the market price for long term electricity, something that otherwise does not exist as derivatives market for power are highly illiquid beyond 5 years.

We’ll discuss the best design for renewable power auctions in a next installment, but the important point to remember here is that spot markets structurally favor generation capacity with high marginal costs, i.e. those that burn fuels, be it coal or gas or others.

It is actually a testimony to how competitive and cheap renewables have become that projects are now getting built on a merchant basis. But it’s not the cheapest way to do it.

Interesting piece as usual Jerome. I am surprised to learn that lenders are so inflexible. Presumably there are some extra steps between ‘prices are too low to service debt’ and ‘banks foreclose on asset’. Is there not a payment holiday function, like a mortgage on a house for homeowners in financial hardship?

Great analysis