Reading the press or comments these days in French or English, the tone about Germany’s energy policies is a mix of the gleeful (of the “schadenfreude” kind) and the contemptuous. Germany was naive (to trust Putin), mercantilist / corrupt (its elite selling their soul or themselves for the “cheap gas” that its industry craves), or in thrall to the perverse ideology of the “commie greens” (who pushed to close nuclear and promote useless renewables).

While it is clear that the current situation, with Russia wilfully reducing gas volumes to Europe, hits Germany quite hard, and will impose harsh choices on its industry and population this year, how much of the above criticism makes sense?

Let’s start with what Germany actually got wrong:

Closing down the nuclear plants prematurely was a mistake - but not so much because of the dependency on Russian gas it creates (more on that below), or because of ideological reasons. No, the core argument here is that nuclear plants should only have been closed after the highly polluting and carbon-spewing lignite plants (many in Eastern Germany) had been closed. Both provide baseload, and lignite should have been seen as a bigger problem than the nuclear plants. But the trend of the Energiewende is to close both, and indeed the lignite plants (production already down 30% over the past 20 years) will close not long - say within 10 years - after the nuclear plants. It would have been smarter to do it the other way round, but domestic political realities (not just pushed by the Greens - they were not in power when the relevant decisions were taken) made it that way.

Allowing Gazprom to own domestic gas storage sites, and to choose how much to fill them (note the link is from August 2021), was incredibly irresponsible. Similarly, letting the percentage of gas coming from Russia go above, say, 30%, let alone 50+%, was, at the very least, naive. When you are importing most of your consumption of a vital commodity, it seems prudent to (i) diversify suppliers, and (ii) build up - and control - storage to deal with disruptions, whether natural or geopolitical. The old Ruhrgas used to know that, but in the liberalized markets of the 2000s, and after the multiple corporate restructuring/M&A/ reorganizations that shook the German power industry, this seems to have been forgotten (I’m not even sure who owns the entity that used to be Ruhrgas these days). The EU imposes ownership clauses on airlines, a little bit of thinking would suggest gas storage is at least as “strategic” - and even if you allow for private ownership of these assets, it would have been easy for the regulator to impose minimum storage requirements on all market participants. That is a failure of policy - but it’s as much a European one as a German one.

Maiming the infant offshore wind industry in 2012-15 because the solar boom at that time (that would be a boon to the whole planet, see below) cost too much to German ratepayers was a stupid self-inflicted wound. The rapid 4 cents/kWh increase to already expensive retail prices that paid for the solar tariffs was made into a political issue - mainly by the liberal FDP. This made the relatively high tariff offered to the (then almost non-existent, and thus costless) offshore wind industry, 150 EUR/MWh, a convenient, if irrelevant, political target.

At the same time, the difficulties of the grid operator to build the grid connections to the first offshore wind projects made the government step in to modify the rules for the connection of new projects: instead of the projects having the automatic right to a connection once permitted and financed, the government would decide which zones would be built and in which order. That was a significant change for developers (who lost control of the timing of their projects, and thus, potentially, saw the value of these projects decline substantially) but it could have been defended overall (with compensation for delayed projects) as a route to ensure an orderly development of the industry and avoid the industrially painful “stop-and-go” of the early years.

But then the government essentially decided (due to the political storm over the feed-in tariffs) not to allow any new zones to be connected (by setting a grid connection target well below what was already built or ready to build), severely undermining the industry just when it was taking off. The tariff regime was also changed towards auctions, but with a lengthy transition period (see a good summary here, PDF). Several years were lost, with almost no construction happening in German waters since 2017. Now everybody acknowledges that offshore wind is the best way to do cheap utility-scale renewables power generation, but it was already obvious to the investors at the time and the government needlessly postponed many GWs of generation capacity with high capacity factors (offshore wind in the North Sea runs on average at 50% of maximum theoretical capacity) that could already be online today.

Not using a real feed-in tariff (or equivalent CfD mechanism). The German feed-in tariff actually acts as a floor (ie if market prices are higher, the producers can keep the upside) rather than a fixed price, which means that when renewables cost less than the market price, the consumers do not benefit from the price hedge that a real fixed price mechanism would offer. Other countries like the UK and France have got that mechanism right, and now benefit from more protection from high energy prices than Germany. This mistake seems about to be repeated in the design for the new offshore wind auctions, which will lead to so called “zero-bids”, and merchant projects that will be, as a result, more expensive, and offer no price hedge to consumers (other than Big Tech).

Against that, there’s a lot of things that Germany got right, and is not getting credit for.

The Energiewende is actually happening, at least in the power sector. The share of renewables in actually generation has gone from essentially nothing in 2000 (a bit of hydro), to 40-50% of the total (depending on how you count biomass and waste-to-energy):

While nuclear has declined (-80% in 2022 compared to the early 2000s), it is notable that the use of coal has gone down significantly as well: -30% for lignite (despite the choice noted above to phase out nuclear baseload first), and -60% for hard coal. There are some upticks in the general downwards trend, and these have been seized upon to say “see, Germany is burning more coal because of its stupid energy policies” but they have always been temporary, and generally linked to lower wind years (like 2010, 2016 or 2021, for instance). In absolute terms, it is even more notable, with coal generation down from 270 TWh in 2001 to 153 TWh in 2021 (- 44%), with overall generation essentially unchanged. Gas generation has been more volatile, but has remained throughout the period in the 10-15% range (as a fraction of overall production).

So the transition from fossil-fuel electricity to renewables is well under way. More importantly, the move from 0% to 40% was done when renewables were expensive and needed supportive policy schemes to happen, in the face of violent hostility by the utilities, whose core generation business was directly threatened by the new entrants. Now that renewables are actually cheaper than any alternative, and fully embraced by utilities after they have essentially depreciated all their legacy assets, and even by oil&gas companies, the rest of the switch is going to be even easier - the only brake today is the lack of permitting, and transmission bottlenecks (also usually permitting related).

The current crisis cannot be solved immediately by renewables, but it would be much worse without them, and with a few more years of continued (and hopefully accelerated) renewable energy growth, outside forces like Russia will no longer be able to influence the power sector.

The cost of Energiewende is often misunderstood and exaggerated - and people forget all that it paid for.

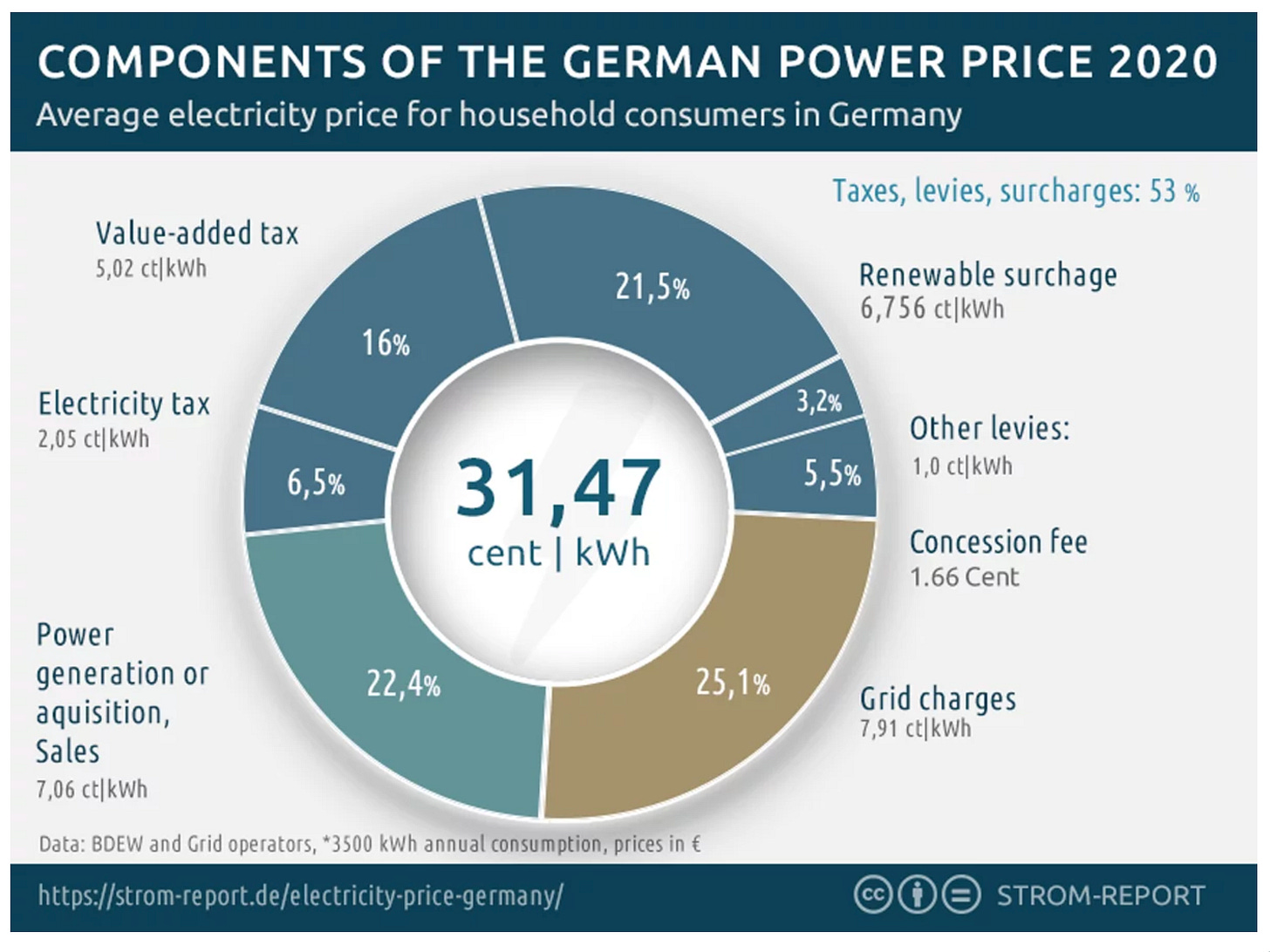

Retail electricity is expensive in Germany, but only a fifth of that (6.8 c/kWh) comes from the “renewables surcharge” that pays for the many years of feed-in tariffs supporting renewable electricity. And three things need to be remembered about that number:

it is a gross cost (ie it does not actually reflect the fact that you get electricity for that, that would otherwise have had to be bought at the then prevailing price), and it applies only to retail consumers (i.e. industry is exempt);

there is extensive literature on the fact that bringing renewables into the system brought down wholesale prices to a larger extent than the surcharge increased retail prices (ie, the prices distribution companies paid for power decreased, the surcharge was de facto paid for through lower revenues for incumbent generators, which explains the enduring hostility of generation-focused utilities to renewables for so long), and

most of that amount comes from the boom in solar capacity in 2009-2011, linked to the high tariffs then available

The ca. 25 GW of solar installed in 2009-12, generating roughly 25 TWh per year, cost something in the order of EUR 10 bn per annum (for 20 years), amounting to more than half of the current renewable surcharge on an ongoing basis. That cost, along with slightly smaller costs borne by Italians and French ratepayers for parallel installation booms, is what made the rapid drop in the cost of solar panels in that period possible - something that benefits the whole planet. German (and Italian and French) ratepayers are subsidizing cheap solar around the world. That EUR 20 bn yearly payment for early projects is Europe’s - and in particular Germany’s - enduring contribution to the energy transition across the globe, and all the countries that can now install ultra-cheap solar should remember that this is only possible because Europeans made that upfront investment 15 years ago and are still paying for it now.

The same happened for wind power, which was less expensive to start with, but has also become cheaper, and for offshore wind, with a spectacular decline from relatively expensive to fully competitive (to the extent it is now being embraced by oil&gas companies).

The willingness of Germans, and some fellow Europeans, to pay for early expensive projects in order to develop the sector and bring the costs down, must be lauded because everybody on the planet benefits even if only the Europeans paid for it.

Furthermore, that cost may not have been so high in the end, as we enter a crisis that has triggered higher energy prices but not a higher cost of renewable energy generation. The bet on fixed long term tariffs suddenly looks a lot more attractive, even if only considering narrow cost grounds, when wholesale prices are at 500 EUR/MWh and seem set to stay there.

We now see stories coming out of France that the renewable energy surcharge (the CSPE) is turning into large budget income for the French government, as per the CRE, the national regulator, with a EUR 9 billion upside for 2022-23, ie 20% of what was paid in the past 15 years for renewable projects - and that’s calculated with price assumptions of 170 EUR/MWh for 2022 and 230 EUR/MWh, well below what market prices are for today or for next year. In countries with strictly fixed prices (so not Germany, as per above), that benefit goes directly to consumers rather than to generators, but even in Germany the money from that power generation stays in the country and does not go to fund external (and potentially hostile) parties.

In other words - the hardest (and most expensive) part of the transition has already been done: we know how to have power systems dominated by renewables, we can now build the generation capacity cheaply, and we can now use that to (i) continue to decarbonize the energy system by reducing the use of fossil fuels to a minimum, and (ii) start decarbonizing other sectors, by electrifying them (electric vehicles, green hydrogen, carbon-free steel, etc). What the sector needs is not money, it’s permits and regulatory consistency.

In that context, there are some criticisms of Germany that need to be perceived differently:

Germany did not sell its soul for “cheap Russian gas”. For a long time, Germany (like France and Italy) purchased Russian gas under long term contracts with prices indexed to oil (and assessed on an “equivalent useful energy content” basis). These contracts were negotiated, since the 1980s, as State-to-State endeavors (even when entered into by notionally private parties on the Western side), and treated as such by all sides - any breach would be treated as a serious bilateral incident between the two countries and brought to the attention of political leadership. They allowed to finance the construction of the pipelines, which tied supplier and consumer together. As only partly commercial contracts, prices tended to be higher than spot prices (but the market in the past was not very developed). France, and to a lesser extent Germany, also imposed storage requirements on the system, that had a cost on the final price of gas.

It was logical to have senior politicians involved in the negotiation - or, later participating to the boards of the joint companies. So while Schröder can rightfully be scolded for his behavior since the war started (and he has indeed been ferociously criticized within Germany), it was still reasonable for someone like him to be involved in the NordStream pipelines, to underpin the political angle in that relationship.

However, from the 1990s and the push for liberalization of the energy markets, the EU Commission (inspired by American and English economic thought, which was developed at a time of surplus domestic gas) tried to promote pan-European markets and fought the long term contracts tooth and nail, as anti-competitive. Existing clauses preventing the resale of the gas by the Western buyers were forced to be dropped, and buyers were generally encouraged to make use of the spot markets, which in times of plentiful gas, were cheaper. Russia did not like these moves, and fought them all the way, but bowed to the inevitable and started selling more volumes on the spot market - and getting involved in the downstream market, buying storage capacity and building distribution capacity. So Germany started buying more and more Russian gas on the spot market rather than under long term contracts. The price was “competitive”, i.e. not necessarily cheap, but market-driven and linked to increasingly widely-traded indexed like TTF. German industry thus benefitted from market prices for energy, like the rest of Europe, not from “cheap gas”.

It is those spot volumes that Gazprom first started withdrawing in 2021 (see again the story from 2021 noted above) - because there was no political price to be paid for the behavior - no contracts were breached, it could all be seen as commercial (if predatory) behavior. So in fact Gazprom’s attack on European gas supplies first came via the parts of the market that were not protected by the (supposedly corrupt) involvement of senior politicians and the long term contracts. This is not on Schröder or other supine politicians, this is on the EU (and Germany) for being naive about energy, treating it as a normally traded commodity and not as a strategic good.

As I noted in an earlier story, and above, it was possible to be a significant importer of Soviet and then Russian gas while taking sufficient strategic precautions to ensure this did not create unreasonable dependency. Poland and the Baltic countries managed to reduce their dependency over time through strategic (and not necessarily cheap) decisions, and Germany should have done the same, but it does not mean that it should have done without Russian gas altogether - and in particular without the long term contracts tied with politicians.

Energy is a commodity with very limited demand elasticity in the short term, and thus it takes very large price hikes to re-balance markets, especially when you have a negative supply shock. This should be obvious from the multiple crises we have gone through over the past 50 years, but politicians still push the gospel of “the markets” for energy while being unable to tolerate the price hikes they necessarily (occasionally) entail, and then imposing market distorting measures (price caps, etc) and looking for scapegoats rather than explain their ideological decisions…

Nuclear will not help, much. There’s a lot of bleating about Germany’s decision to close down its nuclear plants. Ignoring the fact that France’s nuclear production is actually down more this year than Germany’s (without being fully replaced by renewables, in the case of France), the argument is usually that every kWh produced by nuclear would be one less kWh produced by gas-fired plants. The reality is more complex, as nuclear is largely “must run” baseload with little flexibility (just look at any daily chart of generation, and nuclear generation is very flat - it does not adapt at all to demand, even in France most days). Gas, conversely, is increasingly used, alongside hydro (and hard coal in Germany) as flexible generation to plug the gaps between demand and “must-run” plants (nuclear, renewables as per prevailing weather conditions). More nuclear would lead, mainly, to more exports (this year, to France and Switzerland, which use imports and hydro to balance their system), and gas would continue to be used for the fine-tuning of the system. The German economy minister notes that extending the nuclear plants would save about 2% of gas use, i.e. less than 10% of the gas used by the power sector.

It is worth underlining that the volume of gas used in the German system has changed very little over the past 20 years, staying narrowly in a range of 10-15% of overall generation, despite the massive switch (40% and counting) from large lignite and nuclear plants to supposedly unreliable renewables. With hard coal plants (also very flexible) in even larger decline, this suggests that the need for flexible capacity (and thus for gas) has actually declined as nuclear production went down. This is all the more remarkable that this year’s export patterns are increasingly driven by France’s needs, which are for complementary capacity to its exhausted nuclear plants and thus need to be highly flexible, creating more variable demand for the German system.

So, would more nuclear reduce gas consumption? Maybe, to some extent, but definitely not 1-for-1, not even close. So this is not a policy decision that made a significant difference here. In fact, since the proponents of nuclear usually point to France, it can be argued that France’s decision to put all its eggs in the nuclear basket has made it a lot more vulnerable today, as serial defects are found, weather pattern changes trigger restrictions on plant use, and old-age reduces the availability of existing plants. That policy has caused a much larger decrease in generation than the German nuclear fleet, and presumably a (partial) corresponding increase in the consumption of natural gas for power generation, both in France and in neighboring countries that France needs to import from in increasing volumes.

Renewables are part of the solution, not part of the problem. Germany is mocked, as noted, for its supposed focus on a ruinous and ineffective push for renewables that “threw it in the hands of Putin”. I won’t repeat here the arguments above about the fact that renewables are actually reliably providing a large, and continually increasing, fraction of all Germany’s (and Europe’s) power, and are doing so at an increasingly attractive cost. They are also a largely domestic activity, building on the strengths of Germany traditional industry (large mechanical and electrical equipment) and creating more domestic jobs than imports of gas or other fossil fuels ever will. As the numbers from the past 20 years show, renewables do not require more volumes of gas (MWh) for the system to be balanced (they may require more gas-fired capacity (MW), but that’s not the same thing - gas turbines are manufactured in Europe).

So, arguably, and despite the few items outlined in the first part, Germany has been doing largely what we need to - switch towards decarbonated, homegrown renewable energy and away from fossil fuels. It has done so in an way that makes it possible for the rest of the world to follow suit (because its early investment in what then was expensive technology) allowed costs to come down for everybody, even as it bears, along with other Europeans, the price of the early bet on new technology.

It was naive about Russia, but frankly (and I say that as a longtime Russia-watcher), that was not an unreasonable bet to make - Russia has taken an incomprehensible and irrational decision to destroy itself, and even if that cause short term pain in Germany and Europe, it will be way worse for Russia in the long run. But less naivety about Russia would have only helped deal with the short term effects this year, not the long term ones, and for these the Energiewende is and will continue to be the right thing to do.

This is an awesome article and inspired me to start a substack as well.

We need more voices like yours accurately analyzing the German energy system.

Can you please stop repeating this disinformation? Wait for the lignite plants to close and replace nuclear with what? Exactly. Russian natgas. And stop talking about 40-50% of energy mix of renewables, when Germany is using almost every single surrounding country as a "free battery" - they export (dump) solar and wind electricity when it's worse than useless (negative wholesale prices) and reimport nuclear/coal/gas fired electricity when it's necessary. If every country in EU did what Germany had done, we would have daily rolling blackouts across half the EU. Meanwhile France is chilling at somewhat around 30g CO2 per kWh, less than 10% of what Germany or Britain produces to get their kWh of power most of the day. And it's significantly cheaper. So I have no idea on what planet you exist, energiewende is a failure on every single crucial point we should be interested in. Hell, it would be cheaper to take what was spent on energiewende, and pay the absolutely insane prices per kWh it nowadays costs to build nuclear, and in the end you'd have way more actually CO2 free power that you can use (do the math)