Co-written with my colleague Erkan Uysal

This is a topic that has been on our minds for a while now - and one of the reasons we write relatively rarely these days: it seems that nothing one writes will change anybody’s mind, once they have settled on a position.

You belong to a tribe

The notion that people want to belong, adopt a tribe that they are comfortable with (usually because they share their opinion on an issue they care or know about), and then take on the positions of that tribe on topics they know less about, is not new.

For a long time, we were hoping that energy policy could be different - it is fundamentally “real”, driven by physical laws and hard economic realities (things like the price of oil or steel, interest rates, etc), and so in principle, it should be possible to at least agree on some basic facts on the ground, before moving to things that depend on personal and political preferences (appetite for risk, short-term vs long term view, fairness vs efficiency, etc).

But the reality of the energy world is that it is incredibly complex and thus you can easily find real facts that support, or appear to support, almost any position you want to take, and the tribal behavior noted above applies in that sector just as well - and maybe even more strongly because everything about energy policy is political, whether people acknowledge it or not. It touches fundamental human needs (heat, transport, cost of living), core economic issues, sovereignty, geopolitics, and our approach to others and to natural resources.

The energy sector is undergoing massive change and becoming more complex

In that context, a few things stand out:

the energy transition is a major change, and people are (often for good reason) afraid of change. “Better the devil you know”. There are legitimate worries about the cost of new things, and similarly legitimate anguish about how things will work in the future. To give a simple example, people know what it takes, and what it costs, to fuel their car, they are familiar with the availability of gas stations, the maintenance, the resale value of their car, etc. but they don’t know (until they have actually tried it) how all this works for an EV. This can be overcome, but it should not be dismissed as unreasonable

more ominously, that major change impacts, mostly in a detrimental way, some of the largest and strongest corporations on the planet. It is sadly naive to expect that they will let that happen without a fight - and these companies have the ear of top public officials, large PR machines and even some legitimate arguments. Corporations are generally law-abiding entities, but they will certainly do their utmost to ensure that the laws that apply to them are the most favorable, and if that takes pushing biased narratives and facts, or even outright lies, they will not shy away from that. Given their prominence and influence, these feed public opinion and shape the debate

on topics that people do not know, it is possible to shape opinions and sow doubt. “Offshore wind kills whales” has become part of the narrative in US states where no offshore wind exists (and cannot kills whales…), brilliantly neutering people’s willingness to do better (which exists despite the above-noted fear of change) - by generating well-meaning doubt about whether it’s really better. On complex topic that most people don’t really understand in detail, it is possible to use a simple factoid to anchor wider positions (“how do you do surgery when there’s no wind” “we’ll run out of rare earths”). The complexity of energy infrastructure can be used to create moral relativism, and suggest that all solutions have drawbacks anyway, so we might as well stick with those we know and that work - or whose negative consequences we are used to

Zero-sum games vs positive sum games

A wider point is that it looks like the current political battle lines are largely coalescing around different visions of human interactions - basically those who think that they are all zero-sum games, and those who don’t. Or maybe call it a narrow sense of “fairness” against a narrow sense of “efficiency”.

The first category thinks no improvement is possible unless taken from others (and they feel they have been taken from, and thus anything that looks like it’s positive for the other side is bad for them). The second category believes it is possible for everybody to be better off, under the logic of “let’s create the most overall wealth/opportunity/wellbeing in the smartest way, and then redistribute it fairly” - except that a lot of the policies of the past 40 years seem to have focused on the first part (wealth creation) and (willfully or not) forgotten the second (fair redistribution), which is at the heart of the beef the first group has against the second: they have been played, repeatedly, in the name of “progress” and all talk of a greater good are bullshit.

At some point, as wealth became the measure of success and the ultimate goal, wealth creation (non-zero sum) turned into outright wealth capture (zero-sum). In that context, selfishness pays, and you need to protect yourself from the selfishness of others, or be taken advantage of. In particular, you need to be wary of people that promote efficiency or a better future, as it becomes synonymous, more often than not, with sacrifice for you and profits for them in the short term and no improvements later. When one looks at promoters of renewables in that light, it becomes easier to understand the hostility.

That takes us back to the overall complexity of things, and the yearning of people for simple (maybe simplistic) solutions.

One side has simple solutions, and a similarly simple hostility to whatever is proposed by the other side. So what is that other side to do? Accept the current zero-sum nature of the fight, and join that fight with all the energy and, maybe, bad faith necessary to win? Or try to stick to a higher ground which may no longer exist, may not be competitive as such, and is fundamentally undermined by the logic of the first option?

Or refuse the alternative and give up the fight?

Centralisation vs fragmentation

We are actually optimistic in that we see the energy transition as inevitable, because it makes economic sense even in a narrow sense (i.e. even before accounting for the externalities of each solution) and it will happen. It can be slowed down, but it will happen even faster than most people believe. And to be cynical, the people who vote for the status quo are those who will disproportionately bear the consequences of delays and other zero-sum policies, even (and maybe especially) when “their guys” are in power.

In the meantime, the new energy system is becoming more decentralized and it is increasingly possible to have a positive impact at the local level - indeed most changes will be very local and small scale, whether on the generation, storage or demand side, and it is possible to do so whatever the political context is. We are continually impressed by the multiplicity of start up and initiatives happening all over the place - they matter and they will make a difference in aggregate.

They will also make the system more complex than ever - and thus even more subject to simplistic discourse, which should thus mostly be ignored.

We’ll continue to try to write evidence-based pieces, and to acknowledge (maybe even revel in) the complexity of things, but we’ll probably do so sparingly to avoid the unavoidably heated rhetoric of rapid fire commentary.

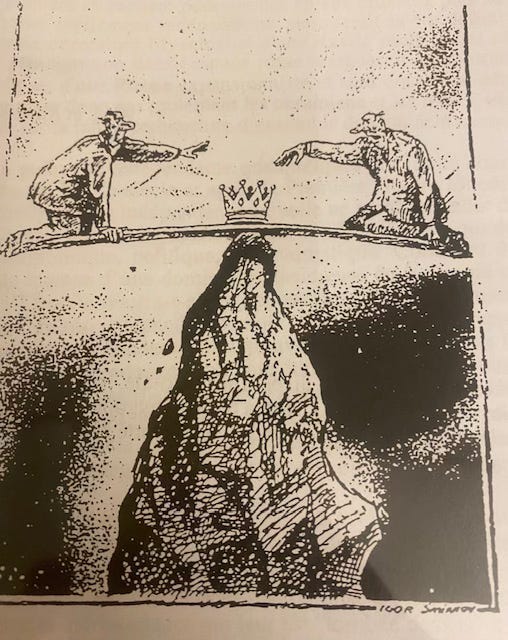

Note: the image above is from a Ukrainian newspaper in 1994 and was used as the cover of Jérôme’s PhD dissertation on the independence of Ukraine…

Excellent observations, thanks

❤️♥️💖